I’m trying to get better at writing out the process for things that I do in my day-to-day metadata work. Mostly, I want to do this for my own personal use – to help me think through my processes more clearly, and to have something to refer back to the next time I want to do something similar. But I’m also aware of how valuable I find other metadata librarians’ descriptions of the work that they do, so I’m going to post this kind of process-oriented writing here on my blog. If you read this and have thoughts, questions, suggestion, I’d love to talk about it with you!

Last month, we finalized the metadata for some additions to a large digital collection of material about Cuban and Cuban-American theater. This particular collection has multiple different fields for creators and contributors (e.g. author, director, cast, costume designer, etc.). Additionally, this collection has been on-going for several years, meaning many people have created metadata for it. Now seemed like a good time to exert some authority control on the names in those various creator and contributor fields, doing some standardization and normalization of names. We use the authorized form of names from LCNAF, for names that have authority records, so my goal was to make sure that all names with LC records used the authorized form, and for all other names, to use one consistent form across all of the fields.

CONTENTdm, which we use to host our digital collections, has an option for individual metadata fields to be set as a “controlled vocabulary,” meaning that we can define a list of terms that are considered valid for that field. Setting the fields I wanted to work on for this project as controlled, with the existing contents of the field used as the list of approved terms, meant that I was able to export a text file for each field with all of the terms it contains. CONTENTdm saves those files on its server, so I was able to easily use FileZilla to download the text files for the 13 fields in question.

I wanted to combine those 13 lists of names into a single list, but add a second column with the original filename, so I could track which names came from which fields. A little googling, and a suspicion that this should be easy to do on the command line, brought me here, and I adapted the script slightly for my purposes: for /f %a in (‘dir /b *.txt’) do for /f “tokens=*” %b in (%a) do echo %b;%a >> all.txt

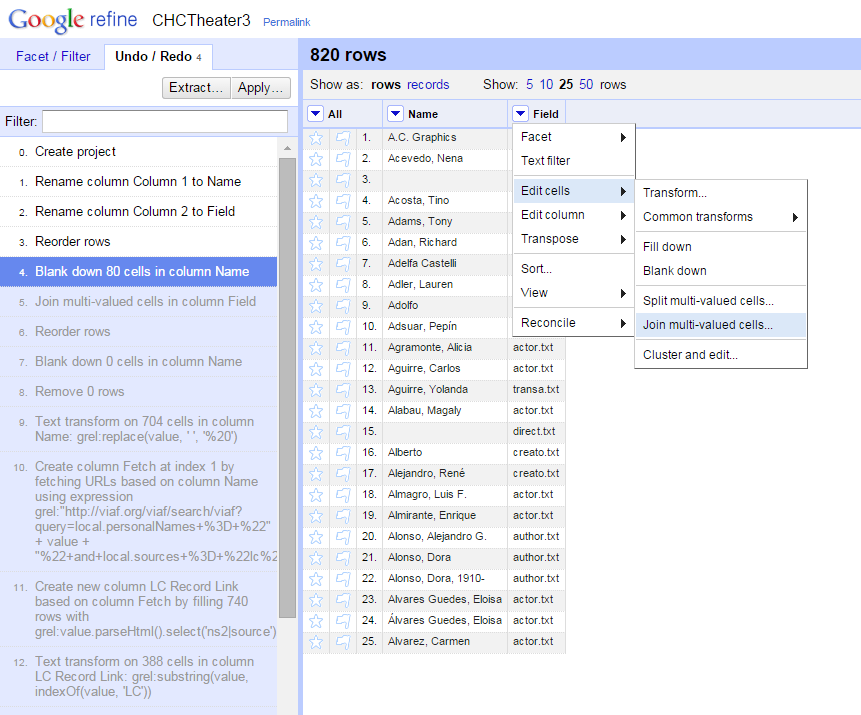

Tah-dah! I now had a semicolon delimited file with columns for the Name and Field. The next step was to de-dupe that list – I needed to find names that were in multiple fields, combine the values from the Field column into one cell, and remove the duplicates. I tried to do this in Exel, and it was a struggle. I briefly considered writing a macro to do it before giving up and doing it manually. I’m glad I didn’t waste a lot of time on a macro for it, because I later realized that it was very simple to do in OpenRefine (thanks to reading Ruth Tillman’s excellent article in the most recent Code4Lib). The way to do it in OpenRefine, for future reference, is:

- Sort by Name, and select “Reorder Permanently” in the Sort menu

- In the Name column menu, under Edit Cells, select “Blank Down”.

- In the Field column menu, under Edit Cells, select “Join multi-valued cells”. That will combine all of the values into one cell, using a selected character as a delimited.

Okay, now the fun part: I had a list of 740 names and what fields they were found in, so I wanted to:

- Reconcile the list of names against LCNAF to make sure we are using the authorized form, if there is one, and

- Identify variant forms of the same name, particularly those that aren’t established in LC.

Fortunately, OpenRefine can help with both of those things!

I tackled reconciliation against LCNAF first. I’d previously tested out a VIAF reconciliation service developed by Jeff Chiu, and had good luck with it. It’s fast, and seems to return good results. I copied the list of names to a new column in Refine, and ran the reconciliation service on that column. After running the reconciliation, I went through quite a few names that had potential matches and manually confirmed (or not) the match, particularly for names that didn’t have qualifiers like dates. I ended up with 98 names that were matched to LC authority records. I created a new column, with only the names that were reconciled with VIAF, using the GREL expression cell.recon.match.name.

My next step was to use the clustering function in Refine to identify potential variants of the same name. I knew there were a lot of potential variants: names missing dates, missing diacritics (or extraneous diacritics), typos, etc. I briefly tried to do this work myself, and quickly realized it was extremely difficult to do. But the power of algorithms came to my rescue! I created another new column of names, and used OpenRefine’s “Cluster and edit” function on it (found under Edit Cells). The clustering function identifies potential variants that represent the same thing and lets you quickly edit them all to one version (or to something else altogether). I tried out various methods of clustering, and found that they caught different potential variants. For each cluster, I chose the correct form and edited the cells to include it. In many cases, this involved going back to the items themselves to verify if, for example, this person used an accent mark. This was a time-consuming process (possibly the most time-consuming single step), because it involved so much looking back at the materials to determine the correct form. However, it wasn’t difficult, and it was SO much easier than if I’d tried to do the matching by hand.

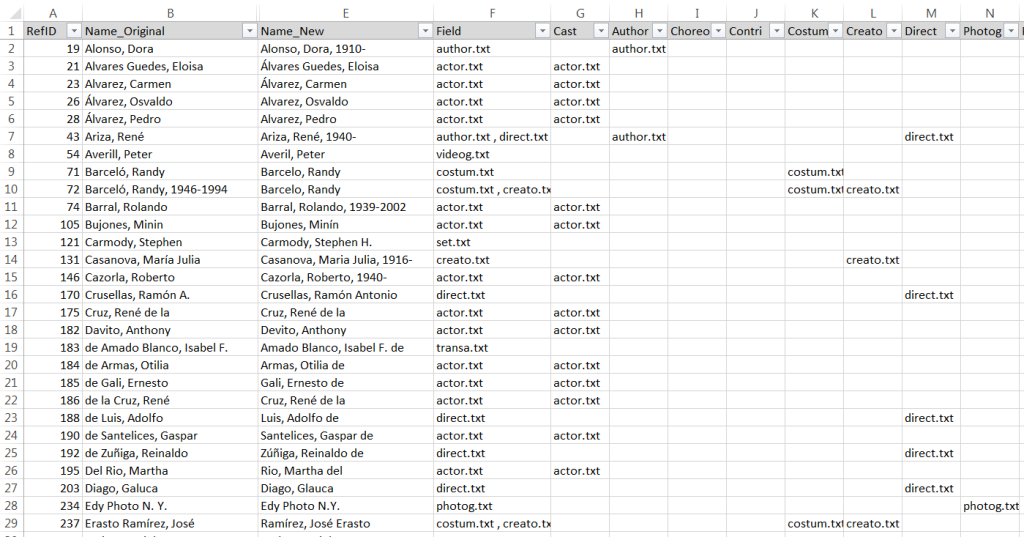

With all of the reconciliation and clustering done, I had my list of names that needed to be edited. I exported the project out of Refine and back into Excel, with colums for the original name, the reconciled name, and the clustered name. I used some IF(ISERROR(MATCH())) formulas to see if the original name matched the values in the reconciled and clustered name columns, and from there was able to separate out the names to be changed. I ended up with a total of 88 names. I then added columns for each original field to indicate if the name was found in that field, allowing me to filter for the names to change in each field.

Last but not least, I went into CONTENTdm and, field by field, edited the controlled vocabulary and used the built-in “Find and replace” tool to update the names that needed to be changed. Because I had a well-organized list of what names needed to be changed in each field, I was able to move through this step fairly quickly.